Keeping it Real

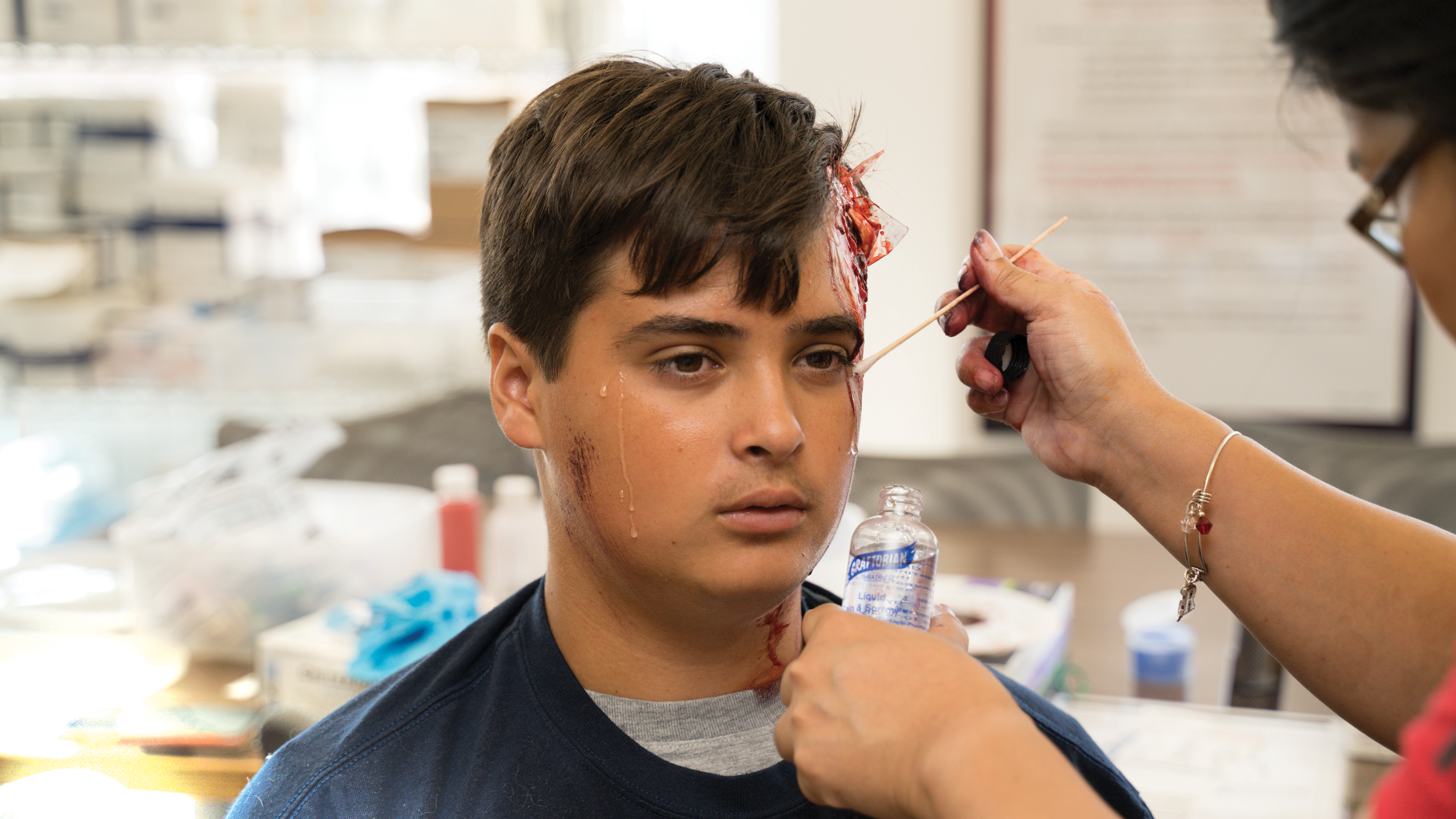

Clinical Learning Coordinator Tita Viray applies makeup to volunteer Gus Filippelli during a disaster nursing simulation.

In the hands of an expert, the technique known as moulage is a powerful teaching tool.

Open the cabinet in the office belonging to Tita Viray (BSN, RN) at the Center for Clinical Learning (CCL) and you may be surprised at the contents, especially if you’re looking for office supplies. In fact, you’re a lot more likely to find vinegar, coffee, canned cherries, gelatin, cooking oil, and other apparently unrelated grocery items, all of which Viray uses in concoctions that help bring to life the physical manifestations of human suffering.

Presiding over what she calls the “sim center” (“sim” for “simulation”) at Rutgers School of Nursing, Viray, whose title is clinical learning coordinator, is responsible for “moulage,” a venerable technique for simulating the appearance of illness and injury through makeup applied either to mannequins or live humans.

It’s an educational tool that dates back to the Renaissance, when it was used on wax figures to teach aspiring physicians. Today it’s employed to train emergency response teams, military personnel, and medical and nursing students. Viray, who’s worked as a moulage artist at the nursing school for the past eight years, uses the items in her cabinet to create simulations that are stunningly—and sometimes shockingly—lifelike.

A Lesson in Three Dimensions

Unlike textbook descriptions and photographs, moulage offers students the opportunity to experience a lesson in three dimensions, to touch it, hear it, even to smell it when odor is added to the effects. “The authenticity of moulage,” Viray says, “gets students immersed in the situation.” And while the students’ requisite clinical rotations offer real-life lessons, not every student on a rotation is likely to encounter rare events like an impalement or a postpartum hemorrhage. With moulage, those encounters are routine.

Kits of readymade latex moulages, as the individual effects are called, are commercially available, but they’re pricey. So Viray often mixes the readymade moulages with her own creations. Those canned cherries become blood clots when crushed and then blended into commercial “blood.” The gelatin, colored with makeup, is transformed into peeling skin. To simulate vernix caseosa—the protective substance that coats the skin of newborns—Viray uses cottage cheese mixed with faux blood.

With their slight sheen, peel-off facial masks—the kind normally used to remove blackheads—make for excellent simulated burns. “I shred the mask, paste it on the skin of the patient with Vaseline, and then add makeup and fake blood,” Viray says. To simulate the look and feel of a deep vein thrombosis—a blood clot, often in the leg, that tends to feel warm to the touch—she heats up the area with a hand-warmer.

Acting the Part

A simulation doesn’t end with the wound. Like a director, Viray instructs her volunteers how to act as if they’re genuinely in pain. They may moan or scream out in distress; their posture and movements may appear hampered by pain or injury. Even the lab’s mannequins offer a fair amount of verisimilitude, opening and closing their eyes and voicing their pain; they’re also hooked up to simulated monitors, so if they’re “bleeding,” for example, their blood pressure will drop and the monitor will clang accordingly.

Because the simulations are so lifelike, students tend to respond viscerally and automatically. If they see blood, for instance, they’ll immediately glove up. “We want to develop those safe habits in the students,” Viray notes. Students are expected to follow whatever simulated cues—in this case, the presence of blood—are offered and respond appropriately, intervening, for instance, to stop the bleeding.

An Essential Learning Tool

Simulations are in great demand at the School of Nursing, but Viray can’t satisfy every professor’s request. “Our greatest challenge is time,” says Debora Tracey (DNP, RN, CNE), assistant professor and assistant dean at the Center for Clinical Learning. Basic simulations take about an hour to set up, and more complex situations—a trauma event, for instance, involving half a dozen patients—can easily take two or more. Cleanup is also time consuming.

Simulations take many forms at the School of Nursing. A popular learning event is the annual Hospital of Horrors that takes place near Halloween. Students go from station to station identifying simulated treatment errors involving 10 mannequin “patients” in varying states of distress, from a construction worker with an impaled leg to a newborn with jaundice.

Like simulated trauma events and other sim center productions, the Hospital of Horrors can sound a little gruesome to an outsider. But for Viray, a successful simulation isn’t about the shock value but about the students’ reactions to her creations. “At the end of the event,” she says, “my reward is that ‘wow’ reaction I inspired and seeing just how much the students have learned.”