From Japan to Jersey, nursing students arrive for disaster training

August 17, 2018

Seven years ago, tragedy struck Northeastern Japan when the Great East Japan Earthquake propelled 133-foot waves onto shore, flattening entire buildings and leaving destruction in its wake. Little was spared, least of all the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which resulted in nuclear meltdowns, radioactive leaks, and hydrogen-air explosions. Displaced residents tallied in the hundreds of thousands as millions went without electricity and water. Though rising tolls have since slowed down, their numbers still loom large: nearly 16,000 dead; more than 6,000 injured; and more than 2,500 still missing, according to a 2018 report by the National Police Agency of Japan.

What could one possibly begin to feel when emerging a survivor amid such loss and calamity? Survivor’s guilt, for one, revealed Tohoku University student Yukiyo Toyokawa, a survivor herself and participant at a recent global trauma simulation held at Rutgers School of Nursing.

Cross-cultural partnership

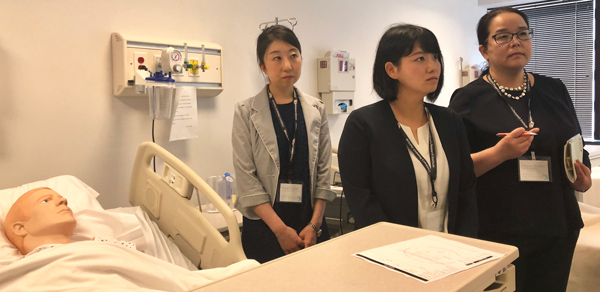

Toyokawa arrived in New Jersey early August with six other nursing students as part of a disaster nursing training program — the fourth team that Rutgers School of Nursing has welcomed from the TOMODACHI Initiative. An international partnership forged in support of Japan’s recovery from the 9.1-magnitude earthquake, the TOMODACHI Initiative trains the next generation of Japanese and American leaders through cross-cultural education. During the disaster training program, sponsored by Johnson & Johnson, participants undertake an intensive U.S. study tour that includes a two-day visit to Rutgers School of Nursing. In recent years, Japanese participants were joined by Rutgers nursing students on the tour.

This year’s agenda included a global trauma simulation at the school’s New Brunswick campus. Tita Viray, clinical learning lab coordinator, transformed Rutgers nursing and health administration students into emergency room patients, using special effects makeup called moulage to create the appearance of train wreck victims and wounded first responders. A proven educational tool, simulations “provide opportunities for students to ask questions as well as allow for a breakdown of each procedure,” said Suzanne Willard (PhD, RN, APN-c, FAAN), associate dean of Global Health and professor. “Faculty can provide real-time feedback and information.”

Through the guidance of Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital staff, the TOMODACHI participants navigated the fast-paced, high-stress energy of an American emergency room as they practiced assessing, comforting, and supporting their patients.

Lessons from Superstorm Sandy

Their disaster nursing training also involved a visit to the Jersey Shore where Seaside Heights Mayor Anthony Vaz and support agency representatives led discussions about ongoing rebuilding efforts following 2012’s Superstorm Sandy, which devastated much of New Jersey’s coast. “I wanted the nursing students to understand that disaster nursing does not just mean assistance directly after a natural disaster or tragic event,” said program coordinator and Clinical Associate Professor Margaret Quinn (DNP, RN, APN-C, CPNP), whose own community was devastated by Sandy. “Rebuilding and recovery take a long time, and as nurses we need to support physical, emotional, and mental healing to our affected communities.”

This nursing care is precisely what led Toyokawa to the field and, eventually, to the disaster training at Rutgers School of Nursing. Following the Great East Japan Earthquake, Toyokawa attended a school lecture where she learned about the long-term effects of disasters, such as psychological impacts and isolation from communities. There, she developed an interest in disaster nursing that replaced her survivor’s guilt with a determination to help her community in the throes of their own trauma. “That disaster pretty much destroyed everything,” explained Toyokawa through a translator. “A lot of people ended up being isolated from their regional communities by going to temporary housing. They had to create a new community. That was hard as well.”

Quinn understands.

“Each year, the students ask what we can all do differently next time. In hoping there is not a next time, we can all be a bit better prepared moving forward, as we have all learned from our experiences and triumphs.”

– Sjuhye Grace Chung